In an article published in April 2024 by The Conversation, Jenny Gore and Drew Miller, from the University of Newcastle shed light on a pressing issue that resonates deeply with us at EdSmart.

The current concerns over teacher shortages in Australia strike at the very heart of our ethos. We believe in the power of education and the pivotal role that teachers play in shaping the future.

Below, we’ve republished an article from The Conversation that we feel gets to crux of the matter and proffers a realistic course of action that we hope will rally others.

Australian schools are facing unsustainable pressures. There are almost daily reports of too many students falling behind and not enough teachers to teach them. Meanwhile, the teachers we do have are stressed, overworked and lack adequate support in the classroom.

Governments are well aware of these challenges and there is no shortage of efforts to tackle them. We have tutoring schemes for students who are struggling, wellbeing programs for burnt-out teachers, and leadership programs to develop senior teachers.

But this approach is uneven: some measures improve, others don’t, some schools see success, others don’t.

Over more than two decades we have refined a process to help teachers improve their teaching. Over the past five years we have been rigorously testing its impact on Australian students and schools.

Our findings suggest it will not only improve teaching but boost teachers’ morale and lift student outcomes at the same time.

Our approach

More than 20 years ago, we developed a framework called the Quality Teaching Model. This is based on decades of research on what kinds of teaching make a difference to student learning. The model is centred on three big ideas:

intellectual quality: students develop a deep understanding of important knowledge

quality learning environment: classrooms are positive and boost learning

significance: learning is connected to students’ lives and the wider world.

Each of these three ideas contains six elements, which are explained in detail in an accompanying guide.

How teachers learn the approach

We then developed “Quality Teaching Rounds”. This is a professional development program in which teachers learn to embed the Quality Teaching Model in the way they teach.

It bring any four teachers together face-to-face or online, within or across schools. They observe and analyse each other’s lessons based on our model. Then they discuss ways to improve their teaching and teaching and learning throughout their school.

It requires at least two teachers per school to attend a two-day workshop followed by four teachers participating in four days of rounds, with no further external input.

The Quality Teaching Rounds program treats teachers as professionals, building on what they already know and do, and honouring the complexity of teaching. It aims to create a non-threatening environment for their development.

It does not dictate particular teaching methods but focuses attention on teachers’ core business: ensuring high-quality student learning experiences.

As a teacher in a regional primary school explains:

"It’s increased our student engagement because suddenly every component of the lesson is differentiated properly. It’s focused on students’ own knowledge and building up their knowledge to the next part."

Our approach enables teachers to work with each other in a non-threatening environment. Tim Gouw/Unsplash, CC BY

Our approach enables teachers to work with each other in a non-threatening environment. Tim Gouw/Unsplash, CC BY

Testing our approach

After a 2014–15 study, we knew Quality Teaching Rounds improved teaching quality and morale. It improved their understanding of good teaching and their professional relationships with colleagues.

But we didn’t yet know if it improved student outcomes.

So, between 2019 and 2023, we have been extensively testing Quality Teaching Rounds. We have tested it using the “gold standard” for research: randomised controlled trials.

This sees participants randomly allocated to either the new or standard (“control”) situation. This allows us to compare whether the new approach makes a difference.

Randomised controlled trials are common in medicine. But they are much rarer in education and require very large samples and are very expensive to run (they are not possible without major government or philanthropic support*).

Our trials involved 1,400 teachers and 14,500 students from 430 schools across New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland.

Testing maths and reading achievement

Our trials measured student achievement in maths and reading in years 3, 4, 5 and 6. We compared results between students whose teachers had been randomly allocated to do Quality Teaching Rounds and control groups of students whose teachers did whatever other professional development was happening in their school.

As well as randomised controlled trials, our research also included case studies, longitudinal research (where we tracked teachers over several years) and evaluation of whole-school approaches embedding Quality Teaching Rounds. This helped understand not only if the approach worked, but how and why.

Across the entire five-year research program, we conducted more than 65,000 student achievement tests, almost 1,500 lesson observations, and more than 27,000 surveys and 400 interviews with students, teachers and school leaders.

We believe no other intervention has been so thoroughly tested in Australian schools or amassed such a comprehensive body of evidence.

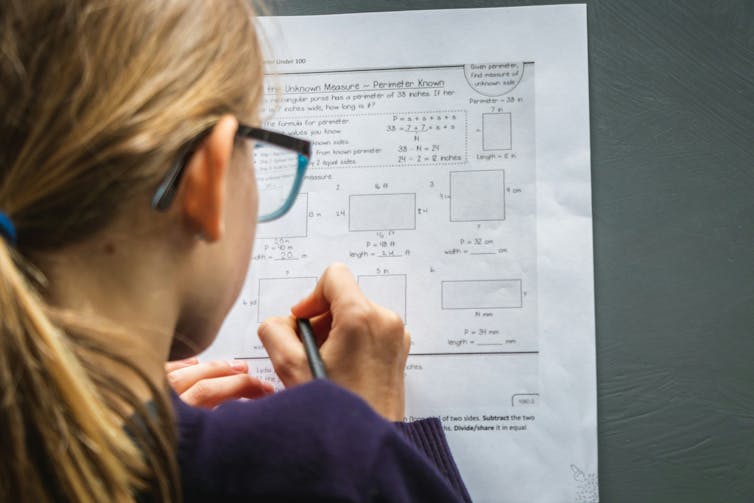

Our trials measured student achievement in maths and reading in years 3, 4, 5 and 6. Greg Rosenke/ Unsplash, CC BY

Our trials measured student achievement in maths and reading in years 3, 4, 5 and 6. Greg Rosenke/ Unsplash, CC BYOur findings

Backing up the 2014–15 trial, we found participation in Quality Teaching Rounds significantly improved teaching quality, teacher morale, teacher efficacy and school culture.

Most importantly, three of the four trials also produced robust evidence of positive effects on student achievement.

This amounted to 2–3 months of additional growth in maths and reading compared with the control groups. Across the studies, such effects were found for students from Year 3 to Year 6, and in both NSW and Queensland. These results were slightly stronger in disadvantaged schools, signalling the potential of Quality Teaching Rounds to contribute to greater equity in education.

As a teacher in a metropolitan primary school told us:

"For my students, I’ve already seen so many improvements in their confidence and in the quality of the work that they’re producing.

Our broader research found this is because the model gives teachers a shared language for understanding good teaching. The rounds then provide sustained time to work on improving teaching, while respecting and empowering teachers.

Because it focuses on the quality of teaching, it works for teachers across different subjects, faculties and school types. In our study, it has been implemented in public and private schools, primary and secondary schools and even universities.

What next?

So far, the federal government has funded 1,600 early-career teachers to do Quality Teaching Rounds between 2023 and 2026, as part of its response to teacher shortages. This is providing access for schools right around the country.

We are also now focusing on a new project designed to support 25 disadvantaged NSW public schools.

Australian governments and education experts know major changes are needed to improve schooling.

Our research shows the Quality Teaching approach has clear potential to address the most pressing concerns – supporting the teaching workforce and achieving excellence and equity for Australian students.

It would cost A$242 million over three years for every teacher in NSW to participate in Quality Teaching Rounds. For comparison, the NSW government invested about $900 million over three years for the catch-up tutoring program for students post-COVID. A December 2023 evaluation found so far, this has had “minimal effect” on student learning.

Schools would still need to make time for teachers to engage in the program. In the middle of a teacher shortage that’s not always simple.

But our research shows the payoffs are worth it. Teachers in our study have already embraced the Quality Teaching Rounds approach: it helps them feel more confident and connected. Perhaps even more importantly, it enhances their work and improves outcomes for their students.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.